By Ana Blanquart

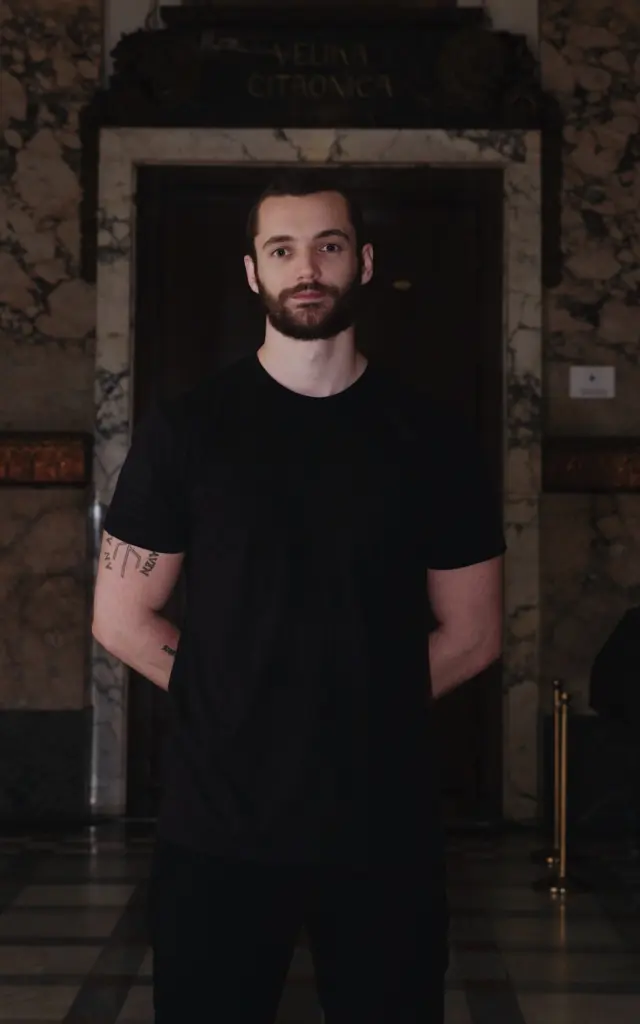

As he slowly strolls through the Croatian State Archives in Zagreb, admiring its painted ceilings and carefully brushing his fingers along antique lamps, Louis Sarkozy looks completely at home. That’s a rare occurrence; Louis avoids noisy bars, shuns expensive restaurants, and despises shopping, so finding a place where he feels relaxed enough to pose for Elle (and he despises being photographed even more than shopping) is a challenge in itself. But places steeped in the spirit of history are his natural habitat. He’s engrossed in archival titles and deep in conversation with our host, asking about the history of Zagreb in detail. This isn’t his first time in Croatia—his wife Natali, who grew up in Africa and studied in France and the U.S., has Croatian heritage and brought him to Zagreb to share childhood memories.

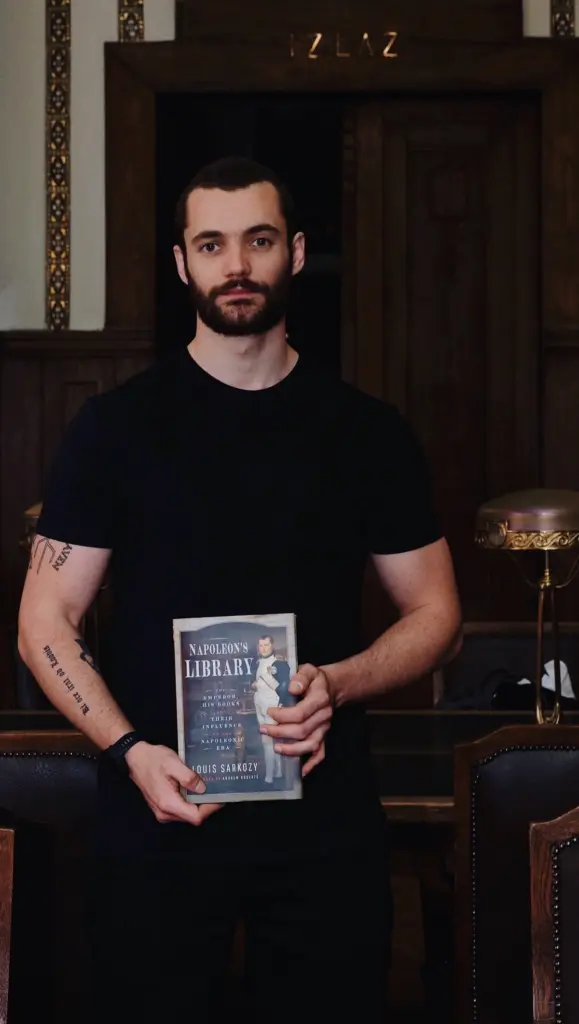

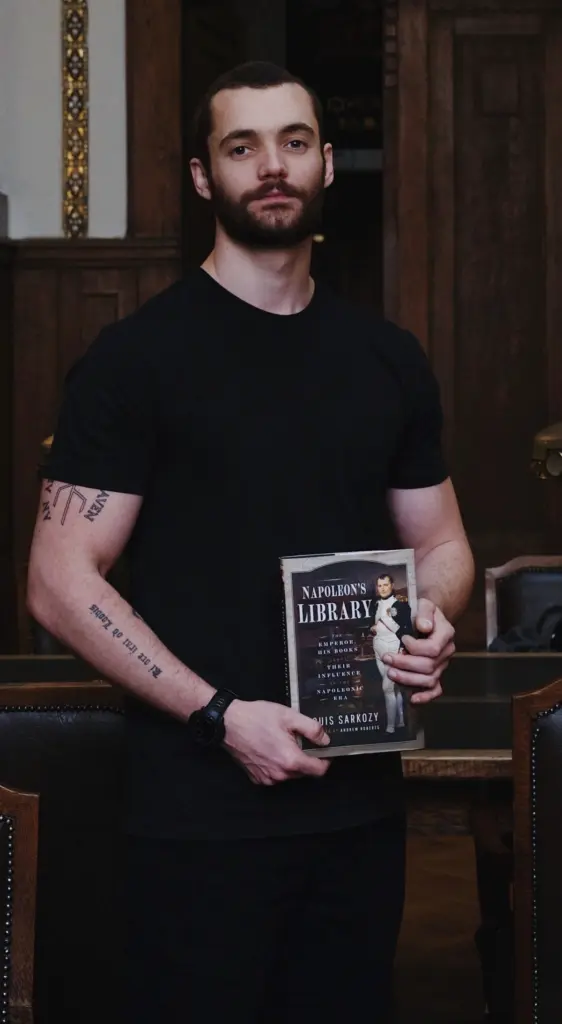

With tattoos peeking from under his sleeves and phrases left over from his military academy days (“Yes, ma’am”), 27-year-old Louis isn’t your typical historian. But contradictions are woven into his personality. Though he bears one of France’s most famous surnames—his father is Nicolas Sarkozy, President of France from 2007 to 2012—Louis now lives in Washington, D.C. His strong American accent masks the fact that he didn’t speak a word of English when he first moved from France to the U.S. It was a jarring leap from the Élysée Palace to a military boarding school, one he says profoundly shaped his character. A man of dual identity—a historian and a soldier—Louis has spent the last three years consumed by his new book, Napoleon’s Library, a study of Napoleon’s lesser-known obsession with books, now being published in the United Kingdom.

How did your obsession with Napoleon begin?

When I was seventeen, I decided I needed to read a biography of Napoleon—I thought, you can’t be a French kid and not know what really happened. I got lucky and picked up a brilliant biography by Andrew Roberts that completely floored me. I hadn’t realized the story was so astonishing, that Napoleon was so energetic, or that his legacy was so vast. It was a total surprise—and at an age when I was hungry for heroes, I found the wildest hero in history.

My wife Natali complains that I go through obsessive phases with historical figures, but this one seems to be sticking. I’m especially proud that Andrew Roberts, whose book first inspired my passion, wrote the foreword to Napoleon’s Library.

What surprised you most in your years of research on Napoleon?

Everything. As a soldier, I’m fascinated by his military campaigns. As a writer, by his educational reforms and the books he read. Had he only been a general, he’d still be a hero. Had he only been a politician, the same. But together, his achievements seem almost superhuman. He was a brilliant general, a statesman, reformer, revolutionary, intellectual, avid reader and writer, and a theorist of theater, literature, philosophy, and music. He touched every sphere of life, reshaped modern France, and transformed Europe forever. I’d argue he’s the most influential figure in world history—and he only lived 51 years.

What did your life look like while writing this book?

There are an unbelievable number of sources—some reliable, many not. More books have been written about Napoleon than any other historical figure. It’s estimated that since his death, one and a half books have been published about him every day. People were so obsessed with him that even those who never met him wrote memoirs. There’s even a memoir by a waiter who once served him wine at dinner in 1804. Of course, much of it is fiction.

That means there’s a lot to read if you want to write about Napoleon. Since my book focuses on what Napoleon read, I had to read a great deal of what he read. I spent months in the French National Library and at the Fondation Napoléon, where I examined nearly 600,000 books from his personal collection. His interests spanned from botany and history to romance novels. Though the final book is short, the research took three years due to the sheer volume—and unreliability—of sources. At times, I felt like I was drowning. Thankfully, I managed to stay afloat.

Many in France wonder why you chose to publish the book in the UK.

The UK has an enormous audience for everything related to Napoleon. There’s a historical fascination with this extraordinary figure. In the House of Lords, where I’m launching my book, the two largest artworks are paintings depicting Napoleon’s defeats at Trafalgar and Waterloo.

Your father was often compared to Napoleon…

There are certainly some similarities—both are dynamic men with an intense drive to accomplish as much as possible. My father is my hero. I admire him deeply. Growing up with someone like him, you have no choice but to give everything your best. Being around him is truly inspiring.

You’re surrounded not only by strong men but strong women too.

Absolutely. My wife Natali is a fascinating woman and an incredible support, as is my mother Cécilia. In the first book I wrote with my mother, we address some of the flaws of modern feminism, which often frames women exclusively as victims of male oppression and as objects in need of male protection. Growing up with a strong mother and now being married to a beautiful, elegant, and intellectual wife, I find that narrative absurd. Women defend themselves just fine. They don’t need the level of protection modern feminists claim they do.

As someone born in France, raised between France and the U.S., with Spanish and Hungarian roots, and a half-Croatian wife raised in Africa—what does “home” mean to you?

The United States. I love my country. I’m incredibly proud to have participated in the tradition of American naturalization. I believe the United States is the most successful political experiment in human history. It’s a wonderful country that has done, and continues to do, a great deal of good for the world. I’m obsessed with American history and constitutionalism. I feel incredibly lucky to live in the U.S. I received my American passport a week after marrying Natali, so I committed myself to both my wife and my country at the same time—and I plan to live in the U.S. with her for the rest of my life.

Still, you were born and raised in Paris. What French traits do you still carry?

I complain constantly. I can’t stand anything from Germany. I eat cheese obsessively. I’m incredibly proud to be French, and this book on Napoleon is a testament to that pride. Though I live in the U.S., I know exactly where I was born and where my roots lie. I feel lucky to be a child of the Atlantic.

Do you think you’d be a different person if your father hadn’t been President while you were growing up?

Absolutely. I’d also be different had I not lived in the U.S. as a teenager and gone to military school. Going from the Élysée Palace to an American military boarding school was a complete cultural and socio-economic shock. Those four years transformed me completely.

What memories do you carry from your childhood in Paris?

It was fascinating—and I wish I had been a bit older to truly appreciate it. To me, the Élysée Palace was simply home. I had a great group of security guards I played with, and I’m still close to them. I even had a LEGO room in the Palace—only recently did I realize that same room now houses framed letters written by Napoleon. Today, I would treat those surroundings with much greater reverence.

Who are your closest friends?

The definition of a historian is: all my friends are dead. I’m joking, of course. Friendship is one of my great passions. I have a large and close circle of friends, many of whom are in the military. That kind of friendship is invaluable—and increasingly rare. There’s no topic we can’t discuss. We’re fully honest with each other, always.

Compared to your generation, you seem to hold rather traditional values?

It’s true. Most people my age are part of the TikTok generation—generally left-leaning, overly sensitive, not very interested in reading or work. That’s sad—and dangerous. But that’s not the whole picture. My generation is also producing deep, intellectual podcasts with audiences in the millions. There’s a vibrant, curious, intellectual youth out there—we just hear less about them. And there have never been more people buying books than today.